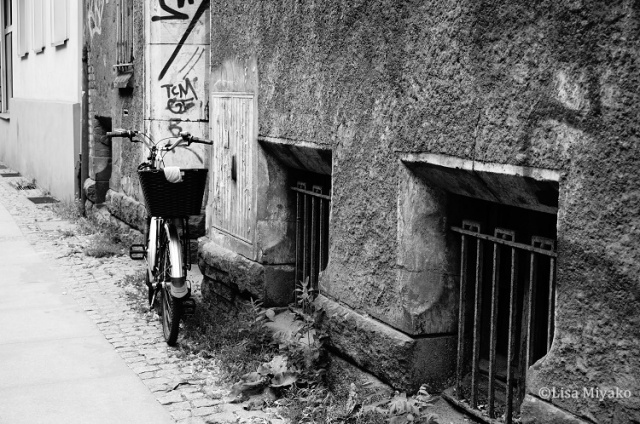

One of my favorite activities is bicycling. I have thousands of photographs from many short bicycle trips around Wrocław and many from an eight-day wycieczka rowerowa (bike tour) along the Baltic Sea coast of Poland (at the end of May that I intend to write about here). Most of the rides are with my friends, Marta (and Łapa) and Tom, and last Sunday, we took a day trip to Milicz. (I am dating this post Sunday, 4 Wreześnia (September), even though the actual of time of posting is nearly a week later.)

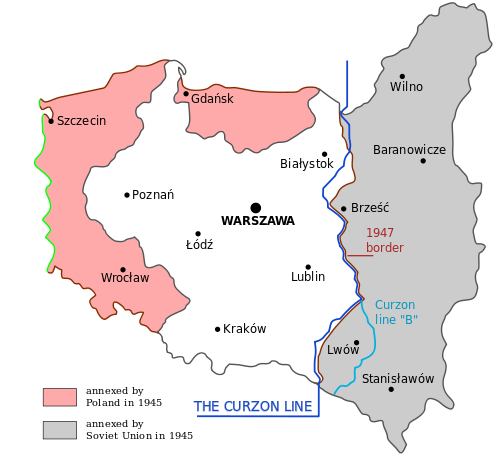

Some recent historical information about western Poland: At the end of World War II, Poland’s borders were redrawn and violently enforced as Stalin and the Red Army took the eastern territory, forcing those Poles westward to populate the former lands of eastern Germany from which the Germans were expelled.

Thus, Wrocław, for instance, is still shown in German airport boards as both Wrocław and Breslau, its former German name. Poland, which is more than a thousand years old, has withstood many territorial shapes.

Back to bicycling and Milicz and a lovely, warm Sunday in early September: Tom, Marta, and I (and Łapa — Łapa always implied) boarded a train at Wrocław Główny for the short trip to Żmigród, about 40km (25 miles) north of Wrocław, where we started our bike ride. Łapa ran alongside us, unless she “hop-hopped” into her przyczepka (trailer), either for a break or because traffic conditions were unsafe for her to run.

ŻMIGRÓD (from Old Polish meaning “Dragon Castle,” formerly Trachenberg). The route Tom planned was to follow DW439, a two-lane highway through the Dolina Baryczy (Baryczy River Valley, Baryczy’s being a tributary of the Odra River), beginning here where we very soon came upon the ruins of Hatzfeld Palace.

0

It was only after looking for information about Żmigród that I understood the significance of this whimsical statue in the ruined palace.

Leaving Żmigród:

That’s Tom in front, then Łapa, then Marta. I, as usual, bring up the rear flank (when Łapa is not riding in the przyczepka attached to my bike), because I stop often to take quick snaps.

Łapa riding in the przyczepka (not pictured) means that I have to lead and set the pace, which means not stopping to take pictures, so now you will have to imagine this road for the next 30 or so kilometers, sometimes passing through vast fields (some flat, some of corn and other crops), sometimes through woods, sometimes through villages, sometimes right next to the river (or some narrow part of it), and one time through a very strong smell of farming (if you know what I mean). It was a beautiful, warm, sunny day with light traffic, perhaps because it was Sunday. Perfect bike-riding conditions.

We passed through villages, such as Radziądz (English speakers, this sounds roughly like “rah’-jones”) and Niezgoda. I laughed when I saw the name of this village and shouted to Marta and Tom, “This is where I should live!” I knew that “zgoda” means agreement, consent, accord. Adding the negative “nie” could only mean we were passing through the village of Discord or Disagreement. Being as I can be contrary, I took ridiculous pleasure out of “Niezgoda.”

Besides, there’s a bike shop.

Leaving Niezgoda heading north.

And along we went, through Łąki (pronounced “wonky” – hehe! I love some of these Polish words!), which means “fields,” appropriately, until we came to Sułów (“sue’-woof”).

Made a left entering Sułów, and lo!

Kościół Matki Boskiej Częstochowskiej.

SUŁÓW (formerly Sulau) is known for two timber-frame churches, the one above, Our Lady of Częstochowa, built 1765-67, and Sts. Peter and Paul, built 1731-34 (which we did not see). Even though it was Sunday, the doors to this church were locked. That sounds like I’m insinuating something, but I’m not, but if I were, it’d be that the villagers were locked inside to prevent them from leaving during the service. But I’m not saying that.

Sułów’s small rynek (town square) serves a population of about 1,400. I used a bit of post-processing in one of those photographs to accentuate the cobblestone road, which can be found even in Wrocław. Imagine riding a bicycle on that. Yeah. We rested for a half-hour before riding the last 9 km to Milicz.

Tom and Marta just before we got back on our bicycles and headed for Milicz.

MILICZ (formerly Militsch). More than a year ago, Marta read Countess Maria von Maltzan‘s autobiography, Bij w werbel i nie lekaj się (Beat the Drum and Do Not Be Afraid) and regaled me with the tales of this heroic woman’s life. The book, originally in German, wasn’t (and isn’t) available in English, I had to be satisfied with Leonard Gross’s The Last Jews in Berlin to read about von Maltzan’s cunning and resourcefulness in helping 60 Jews escape Berlin during WWII.

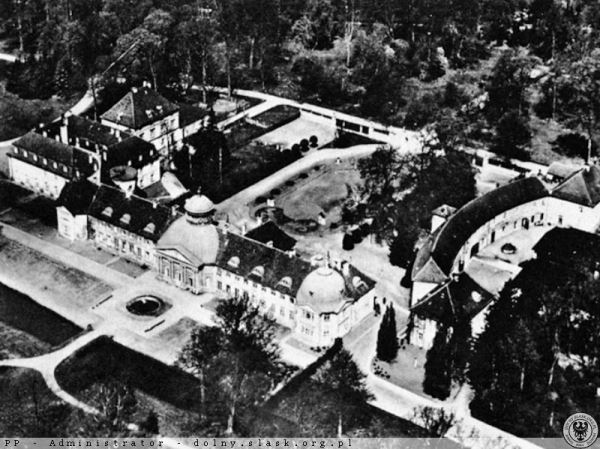

Maria, the last of eight children, spent her childhood exploring her aristocratic family’s 18,000-acre estate, land that was given to the family in 1590. When we realized that Milicz was only 60 km from Wrocław, we determined to make a kind of pilgrimage. And so today, we rode through the humble gate and saw this:

Pałac Maltzanów

Incredible. Marta and I were giddy, telling each other what we’d remembered about the gutsy Maria. Marta remembered more, as the autobiography addressed, of course, much more of Maria von Maltzan’s childhood than Gross’s book did. We kept grinning to each other. Maria’s childhood home! Marta spoke with an older couple on bikes, telling them about Maria von Maltzan. I didn’t pay attention, because Polish. (I’m cobbling sentences together, able to speak the words slowly, but still lost when listening.) Then Marta said to me, “This is the back!” Following directions, she led us to the front.

Łapa trotting up the driveway as if she lives here.

Even more impressive! Pałac Maltzanów is now a technical school, teaching forest management. As we walked around, Marta told me that one of her cousins, a forest ranger, had attended this school. I bit back on envy. Then I remembered how, during our eight-day wycieczka rowerowa a few months ago, Nature tried to kill me, or at least scar me for life, with swarms of horseflies and mosquitoes as we struggled to drag our bicycles through a swamp (by the way, part of the Euro Bike Path, thanks, Poland), and the envy disappeared.

My bike and me in the reflection of a von Maltzan window.

A photo of Pałac Maltzanów via dolny-slask.org.pl

We poked around for a bit before heading southwest for Trzebnica, about 35 km away. We figured the ride down would be as easy as the ride up and that we would pedal all the way to Wrocław, another 20 km south. Easy.

Excuse me for a moment. I must laugh. I must laugh and shake my head and stop laughing.

The WIND!

My god, the wind. Wiatr, in Polish. Not just A wind. A powerful, curse-inducing, pedalling-downhill/no-coasting sonofabitch WIND. (Tom cursed the wind, he told us later, after we caught up with him at Trzebnica where he sat on a bench, looking comfortable and possibly amused.) Not to mention the route, DK15, is hilly.

Yes, Marta hooked the przyczepka to her bicycle to give me a break – twice, for maybe 3 km each time – and she struggled worse than I did. I have to admit, I of the Power Thighs, do ride a lighter, speedier bike, even with the przyczepka. The “admit” part is that I was gratified to see Marta struggle, because it meant it wasn’t me; I wasn’t weak.. She kept complaining about the wind, but I didn’t feel it on my face so much as in my quads and calves. Maybe because my skin was covered by dried perspiration (or salt — Marta laughed at me, said that I had to white lines of salt on my neck. “Like lines of cocaine?” I said. She nodded and kept laughing.)–I mean, I felt some wind, but I didn’t expect it to give us so much trouble.

We crept along between 12- and 18-kph–on the two-lane highway that was much busier than DW439. As we entered TRZEBNICA (formerly Trebnitz), I found finally a safe spot to pull over and looked back at all the trucks and cars that had gathered behind us (in less than a few minutes, because the back-up wasn’t that long until the truck couldn’t pass us). That was the only time we presented a delay (and of less than a minute!) for drivers, something I am always aware of, coming from the San Francisco Bay Area where even a moment’s delay can enrage drivers who will then attempt some kind of vehicular retaliation. I’m glad to say that no one even honked or showed any impatience — thank you, civilized drivers of DK15.

So–no pictures. It was beautiful, though. Pretty sure.

Marta and I joined Tom on the bench to rest and laugh about that crazy-strong wind (Łapa laid out on the dirt and weeds, legs splayed front and back, as if she were sunbathing on a St. Tropez beach — I love her imagination) and readily agreed to take the train the rest of the way to Wrocław. That settled, we sat for a few more minutes. Tom pointed to a tower and said that that was the monastery that Trzebnica is famous for, Sanctuary of St. Jadwiga (Hedwig), and that he’d wanted to show us. He looked at his watch (17:00), checked the train schedule (trains at 17:49 and 20:00-something), and we all instantly chose the 17:49 option. Tom laughed at the lack of niezgoda.

As we rode to the train station, I felt a few drops of rain on my face and shoulders.

Trzebnica train station.

We waited outside by the tracks with others heading in our direction, feeling great about our bike ride, even with the wind, talking about the steep hill between Trzebnica and Wrocław (I am willing to face that hill, see it for myself; also, down hill, duh.), and already planning the next day trip.

Łapa. Anywhere’s fine, as long as she’s in front.

Almost as soon as the train pulled out of the station, the downpour began. We watched the storm and the wind and lightning from the dry side of the windows and wondered how drenched we might get riding our bikes from Wrocław Główny to our respective homes. Less than an hour later, we disembarked the train…storm over. The storm left the city dripping wet and with puddles reflecting the early evening sun going down. We got on our bikes and pedalled home, grinning, I’m sure, like the luckiest bastids of the day.

Total km: 72.46 on bikes.